MYRTIS LEE HEARD JACKSON – HER FAMILY AND LIFE

(I wrote this in the summer of 2012, and never finished it. I found it, and decided to publish it even though it is not yet complete.)

|

| Myrtis Lee Heard while in Graduate School at LSU |

OBJECTIVES-- Myrtis Lee Heard

Jackson was born on Aug. 8. 1912 and died on April 11, 1995, having lived almost

83 years. The 100th Anniversary of her birth will occur this

month. This approaching “birthday” and

other recent events have left me reminiscing and missing her so much. More than anything I wish I had “known,” really “known” my mother. I can

recite the events and important dates of her life; I can recount my memories of

things she did and said; but I am uncertain as to how much these allow me to

actually understand who she was. In

writing this Blog, I hope to accomplish two things:

1.

To bring together what I know of Myrtis Lee --

to explore, organize, synthesize, summarize, analyze, and maybe, just maybe

gain more insight.

2.

TO ASK YOU – my readers to share your thoughts

and experiences in order to expand and explore the mosaic that was Myrtis Lee’s

life. To this purpose, I invite your

responses and comments. PLEASE

CONTRIBUTE.

THIRD GOAL -- We may or may not

achieve these two ambitious goals, but in our efforts, I am fairly certain we

can achieve a third and equally important objective – to leave some stories and

impressions for Myrtis Lee’s great grandchildren – Veronica, Patrick, Carlos,

Sarah, Alex, and Brody. Myrtis Lee lived

to hold the two oldest, but only Veronica has any memory of her. Kyle and Roni Jackson were expecting Alex

while Myrtis Lee lay dying, and she taped a picture of the expectant couple

exactly where her eyes rested as she lay in the most comfortable position

afforded her. I found the photo after

her death, and knew it was the image impressed on her heart at the end. On one character attribute there can be no

doubt – Myrtis Lee loved her family; the family she grew up in and the family

she created with Wilmer “Jack” Jackson, Sr.

The second attribute which cannot

be denied, was her love of teaching of the children she taught.

TO THE READERS -- To begin at the

end, I remember that on April 12, 1995, as my mother lay in the funeral parlor

in Logansport, a steady stream of people passed through. Most had a story they wanted to share -- a story about my mother, and what she

meant to them. When I went to bed that

evening, I knew that I would be burying someone I had never really known. She was my beloved Mother, and that was the way

I knew her. All these other people knew

other aspects of her; other facets of the total person. They had offered me new insights, new

knowledge of the complex person I had called Mother for 62 years. I am hoping that some of those who shared

their stories on that occasion and others who have not shared their stories,

will take this opportunity to share stories about Myrtis Lee. DO IT NOW.

Just go the end and add your story.

Even if you decide not to dig through all that I have written, please

write your entry. THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR

CARING AND SHARING.

If you are like most people, you

have had the experience of sharing deeply with some stranger http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consequential_strangers;

http://faculty.kent.edu/ehollen2/reappointment/CPHollenbaughEverett2011_anonymity

.

Sometimes these encounters happen on a plane or train, at a conference, on a vacation, on the internet, or on a Blog. In a disconnection from ordinary, daily life, two strangers engage in a conversation in which they reveal their deepest fears, hopes, desires, disappointments, joys. With a stranger, whom we don’t know and will probably never meet again, there is a sense of “safety” a freedom to reveal what we normally keep hidden. Is it possible for us to engage in such revelation with someone with whom we have a long and intimate relationship; or do the very demands of that relationship preclude openness and self-revelation? Can we ever really know those who are most close and dear to us? Most of us want those we love to see only the best in us. Most of us want to know only the best about those we love, and are often deaf, and blind to their failings. We all participate in conspiracies that restrict and define how well and how deeply we actually know those we love. I guess I am asking whether a Mother can (or should) know her daughter; and whether a daughter can ever really know her Mother. Are we doomed to have less appreciation and understanding for those we love most? I know that I would give anything to engage today in a deep and personally meaningful conversation with my mother; but I also know that I would be deeply frightened about engaging in such a conversation with one of my daughters. Can we transcend this paradox, and achieve greater empathy and understanding of those we love. This is an eternal question in human existence. It won’t be answered, but it can be addressed.

Sometimes these encounters happen on a plane or train, at a conference, on a vacation, on the internet, or on a Blog. In a disconnection from ordinary, daily life, two strangers engage in a conversation in which they reveal their deepest fears, hopes, desires, disappointments, joys. With a stranger, whom we don’t know and will probably never meet again, there is a sense of “safety” a freedom to reveal what we normally keep hidden. Is it possible for us to engage in such revelation with someone with whom we have a long and intimate relationship; or do the very demands of that relationship preclude openness and self-revelation? Can we ever really know those who are most close and dear to us? Most of us want those we love to see only the best in us. Most of us want to know only the best about those we love, and are often deaf, and blind to their failings. We all participate in conspiracies that restrict and define how well and how deeply we actually know those we love. I guess I am asking whether a Mother can (or should) know her daughter; and whether a daughter can ever really know her Mother. Are we doomed to have less appreciation and understanding for those we love most? I know that I would give anything to engage today in a deep and personally meaningful conversation with my mother; but I also know that I would be deeply frightened about engaging in such a conversation with one of my daughters. Can we transcend this paradox, and achieve greater empathy and understanding of those we love. This is an eternal question in human existence. It won’t be answered, but it can be addressed.

|

| Myrtis Lee Heard as an Undergraduate at Louisiana Tech |

LIFE AND TIMES --

My Mother, Myrtis Lee Heard Jackson

was the 8th of 13 children born to James Addison Heard and Clora

Frances Nolen Heard. Her Father was a

graduate of the first Louisiana Normal College in Lake Charles and taught until

he couldn’t support his growing family on a teacher’s pay. He then became a surveyor and timber buyer

for the sawmills that cut the long leaf pines of southwestern Louisiana. Her mother raised the children and ran the

farm outside of Pitkin, LA.

|

| James Addison Heard |

Her paternal Grandparents, John

Thomas Heard and Sarah Adeline Lindsey Heard were early pioneers and residents

of Dry Creek; while her maternal Grandparents Merida Tilus “Til” Nolen and Maria

Theresa Jones Nolen grew up in Surgartown, and moved to Pitkin after their

marriage. Til Nolen grew up in poverty

after his father was murdered by a group of “home guard” during the Civil War. However, Til achieved prosperity and owned a

large farm and the Pitkin Mercantile (hardware and dry goods) Store in

Pitkin. After his marriage to Clora

Nolen, James Addison Heard homesteaded a farm adjacent to his father-in-law’s

property, and built a home for his family.

This farm is owned and maintained until this day by their

descendants.

It is a challenge for us today to

comprehend the dynamics of growing up in a large family in rural Southwest

Louisiana during the early decades of the 20th Century. Just consider: Myrtis Lee’s oldest brother

was born in the 19th Century and two of her siblings lived into the

second decade of the 21st Century. Collectively, James Addison Heard and Clora

Nolen Heard have over 100 descendants spread over six living generations.

I confess that the complex dynamics

of sibling relationships has fascinated me since I began to realize that my

Heard Aunts and Uncles had patterns of differing relationships. Some of my cousins and I have discussed this

topic and can identify two distinct patterns among the 12 Heard siblings: First, there are the “Playmate” groups (those

siblings who were close in age, and played and grew up together); and Second,

there are the sibling parent/baby pairs (in which an older sibling assumed a

parental role in the rearing of a younger sibling).

The Oldest playmate group consisted

of T. P., France, Addie, Glenn and Rufus.

Rufus was the swing man in this group, belonging both the oldest

playmate group and to the Middle playmate group, which consisted of Burkett,

Simmie, Myrtis Lee, and Vera. The Younger

playmate group consisted of Meredith, Alton, and Lindsey. Interestingly, this “younger” playmate group

was supplemented by the oldest grandchildren, Hewell and Jerry, who spent the

summers and holidays with their Uncles on the farm. Hewell was the same age as Lindsey, and Jerry

was only two years younger.

Myrtis Lee’s oldest brother fought in the 1st World War. Thomas P. “Red or Skipper” Heard returned and entered LSU, where he came to the

attention of a number of influential people, including Huey Long. He worked as the first trainer for the LSU

Tiger football team, and after receiving his bachelor’s degree, he managed the

business of LSU sports (http://communicatinglife2.blogspot.com/2011/06/thomas-pinkney-heard-pink-red-tp.html).

Huey, later made him the first Athletic Director at LSU. Her second brother, Frances Hewell “France” married and settled in Ruston, LA. to raise his family. Her oldest sister (10 years her senior), Adeline Theresa “Addie” became a teacher and taught in schools near the family home in Pitkin. Addie was Myrtis Lee’s teacher and basketball coach in high school.

Huey, later made him the first Athletic Director at LSU. Her second brother, Frances Hewell “France” married and settled in Ruston, LA. to raise his family. Her oldest sister (10 years her senior), Adeline Theresa “Addie” became a teacher and taught in schools near the family home in Pitkin. Addie was Myrtis Lee’s teacher and basketball coach in high school.

Addie

taught during the school year, and went to school in the summers, advancing from

a high school degree, to a two- year Normal teaching degree, to a full

Bachelor’s degree. These were the

depression years, and Addie was fired from one teaching position because she

was a single woman, and a man (with lesser qualifications) needed her job to support

his family. Addie was an outstanding

basketball coach, and coached a state championship girls’ team in 1923. Addie taught almost every grade at some time,

but eventually decided she preferred first graders. After many years of teaching, she attained a

master’s degree. She taught in Louisiana

and Texas schools for almost 50 years.

For a woman

who wasn’t allowed to vote until she was 38, Clora Frances Nolen Heard had an

interesting gender philosophy. Clora

said she hoped her sons would seek an education; but that she would see that

her daughters finished college. She held

that men could do quite well in the world without advanced education, but that

a woman’s best hope for a good life was education. Clora fulfilled her pledge -- all three of her

daughters finished college, and two went on to complete graduate degrees.

Clora

Frances Nolen was a woman who looked life straight in the eye and never

flinched. She was barely 5 feet tall with

flaming red hair, and she ran the Heard farm, primarily with labor birthed from her

own body. When anyone in the community

was ill, Clora was called in to provide care.

She was also the local midwife.

Clora knew a great deal about quarantine, transmission, and prevention of

diseases. When Myrtis Lee contacted typhoid,

Clora identified the bad well and closed it.

She isolated Myrtis Lee, and sterilized everything the infected child

touched. None of the other children

contacted the disease.

Clora was also the one called in to

tend to the dying and the dead. She

closed many eyes, and washed and clothed bodies for burial. She never considered these services to be

less than natural. Clora had only

distain for those who avoided or denied the unpleasant aspects of life. If you said something foolish or downright

stupid, she would look at you with a mixture of pity and scorn and say, “Aw

pshaw.” You did not want to speak

nonsense, lies, nor bull-shit to Maw Maw Heard.

Clora Heard practiced an amazingly

effective form of disease prevention for her children and grandchildren. She maintained a cabinet of the most vile

smelling and tasting medicines known to man.

Most were either laxatives and purgatives or antidiarrheals. They ranged from castor oil, milk of

magnesia, and versions of senokot to kaopectate. She also had a supply of equally vile cough

and fever remedies. If a child (or

grandchild) had a minor complaint, out came the medicines. Grandmother Heard felt that a

laxative/purgative was appropriate for everything except diarrhea. As she put it, everyone needs a good

“cleaning out” from time to time.

Needless to say, the children in Grandmother Heard’s care quickly

learned not to have any minor illnesses.

We did not complain unless we were near death or in great pain. In those cases, Grandmother Heard’s response

was quite different. The sufferer

received both sympathy and tender care.

Her most frequent medicines for pain were paregoric or a hot toddy made

with good Irish whiskey. I still

remember my Grandmother’s tender and effective care for my earaches and

menstrual cramps. Till this day, the

smell of a hot toddy brings her image, and feelings of warmth and security.

While

Myrtis Lee was still in school, and Addie was teaching, the Heard home burned,

and the family lost most of their belongings, including furniture and

clothing. James Addison Heard received

burns on his face and torso while trying to rescue valuables from the burning

home. Myrtis Lee said that the children

left home for school in the morning, and returned to a burned out shell in the

afternoon. It was a tragic, and

unforgettable event for the family. They

built a smaller home (since several of the children were now grown), across the

field from the burned home. This second house

still stands on the Heard Farm outside Pitkin, La. Bricks

from the original home were used in the construction of the fireplace in the

newer home. Some of these bricks are in

the hearth of the fireplace in our house in Joaquin.

Initially,

Myrtis Lee did not want to teach. She

opted for the only other profession open to women of that era – nursing. Her grandmother, Maria Theresa Jones Nolen,

held an old fashioned view of nurses, as little better than prostitutes, and

would not speak to Myrtis Lee when she left for nursing training.

Rejection

by her Grandmother Nolen was very painful for Myrtis Lee. She had always been close to her Grandmother,

whose farm was adjacent to the Heard property.

Maria Theresa Jones Nolen was an aristocrat, and matriarch of her

family. Married at 19, she lost four

babies at birth or in early infancy; and raised three daughters and two

sons. Her father, William Jones died when

she was 8 leaving her mother with four children to raise. William was a prosperous farmer, who lost

everything after the Civil War, dying in 1865 with few remaining financial

resources. In spite of (or maybe because

of) their poverty, Maria held tight to pride in her Jones and Jelks family

heritages. While deprived of their opportunities

for education, Maria and her brother Robert made certain that their children received

educations in the local schools. Robert’s son Sam Houston Jones became a lawyer

and was elected Governor of Louisiana in 1940.

Sam served one term, cleaning out much of the corruption of the Long

Machine, and instituting the Civil Service system for state employees (thus

eliminating the “spoils” system in state jobs).

The Jones family were staunch Democrats, but consistently opposed the

Longs.

Maria Jones Nolen held education in

high esteem, supported women’s suffrage, and wanted equal treatment for her

daughters. Her husband left his land and

businesses to his widow and his sons.

After his death, Maria gave her daughters equal shares in the estate. She was fond of her son-in-law James Addison

Heard because he was an educated man.

She was quoted by her grandchildren as saying that she wished she had an

education. Specifically, she said that

with an education she might have been able to say what she wished to say

without offending and alienating people.

In short, Grandmother Nolen was a woman who “told it like she saw it,” and the listener could like it or

not. From the stories I have heard, I

don’t think a better vocabulary would have solved Grandmother Nolen’s

communication problems. Her descendants,

with far better educations, still find it difficult to sugar-coat the truth or

keep quiet when others spout nonsense.

Grandmother Nolen lacked tact, and had a low tolerance for

bull-shit. Most people either loved and admired

her or hated her. Clora, Addie, Myrtis

Lee and Vera had many of her traits, and some of these may (just may) have been

transmitted to her granddaughters and great granddaughters.

It was her Grandmother Nolen’a opposition that

prevented Myrtis Lee from leaving nursing school after the first few

weeks. The nursing school was a Catholic

educational program, run by the nuns with rules that were restrictive even for

the early 1930’s. The nuns were making

sure that their nurses were not mistaken for loose women. Myrtis Lee hated the rules and restrictive

life, but stubbornly stuck it out. She

just wouldn’t return home to her Grandmother’s, “I told you so.”

Myrtis Lee learned a lot from that

year as a nurse –in-training. All of her

life, she gave shots for family members (especially diabetics), and provided

bedside care to ailing family members, including those who were dying. She never flinched, nor turned away from the

hardest, most emotionally devastating aspects of illness and death. Her loving face was the last earthly sight

for many.

After a

year of nursing school, Myrtis Lee returned home briefly, and then accepted an

invitation from her brother France and sister-in-law Bessie to join their

household in Ruston, where she would attend Louisiana Tech. Jesse Burkett Heard, who was four years older

than Myrtis Lee was also living in Ruston, where he had recently married Lois

Glenn Barker. Burkett worked at

Louisiana Tech for over 50 years. His

daughter, Bette Lois Heard Wallace and grandson Sam Wallace have also made

careers at the University.

Stories of this time in Ruston were

told by Myrtis’ nephews Hewell and Jarrell “Jerry.” Myrtis

lived part of her time at Tech in the dorms and part of the time in her brothers’

homes. The boys remember her as lively

and adventurous. They tell a great tale

of the day Bonnie and Clyde were shot

(May 23, 1934). When word of the

shooting reached Ruston, Myrtis Lee wanted to go see the excitement. She and Bessie and the boys drove to Arcadia

where they saw the bullet-riddled Ford in which the outlaws died. However, the bodies of Bonnie and Clyde were

laid-out inside a building, and closed to the public. Myrtis Lee and the boys slipped around to the

back of the building, and managed to lift and boost each other up so that one

at a time, they could look in a high window to see the bodies laid out on a table.

Jerry vividly remembered Myrtis Lee

winning swimming and diving contests held at LA Tech. The boys were so proud of their petite Aunt

(5’1”, less than 100 pounds) who swam faster and dove better than the older,

larger girls. Her victory was more

remarkable because she had never had opportunities to swim in a pool. Her swimming was done in Six-Mile Creek, and

her diving was perfected on tree branches over-hanging the swimming hole.

At Louisiana Tech, Myrtis Lee

majored in English, but the teaching certificate she received covered all

grades, elementary through high school.

She taught one year (I believe) before accepting an invitation from her

oldest brother, T.P. “Red” Heard to come to Baton Rouge for graduate studies at

LSU. As Athletic Director (in an era

when nepotism was an accepted part of the culture) Red gave Myrtis Lee a job in

his office where she worked for his assistant, Bernice Golden. Her

brother was called Red, so Myrtis Lee became “Little Red,” a nickname used by many of her fellow students and colleagues.

Myrtis Lee was not the only Heard

daughter at LSU that fall,. Vera Ruth

Heard (three years younger) was also at LSU, and they lived together. As an undergraduate, Vera had a job in the

Post Office. The sisters were frequent

visitors in the home of their older brother and his wife Elizabeth McKnight

Heard., and became close to their nieces and nephews, Harriet “Sister,”

Tommie, Florence Adele, and Robert.

The two sisters, who came to look

much alike in their later years, were quite different in their youthful appearance. Vera was a taller than Myrtis, and very slim

with dark hair and deep dimples. Myrtis

Lee had dark auburn (mahogany-toned) hair and was shorter and more curvaceous. It irked both sisters that most people

assumed that Vera was older. Myrtis Lee kept a photograph album from this

era, with pictures of the two sisters with friends and suitors.

It was an exciting time at LSU. The sports teams were winning; and state monies,

invested in hiring the best academics, were building the university’s

reputation. Many of the photos in

Myrtis’ book include famous athletes who played for LSU during the 1930’s. During this time, Red introduced lights and

night games to college sports. On at

least one occasion, Huey Long charted a train so LSU students could travel to

see the Tigers play in a bowl game. Myrtis

Lee and Vera went on the first such

excursion, and also helped raise money to buy the very first “Mike The Tiger.”

Myrtis Lee changed her educational

direction at LSU, pursuing a master’s degree in physical education. Pictures from the era show her playing a

variety of sports, including basketball, gymnastics, archery, modern dance,

medicine ball exercise, golf, tennis, rowing, swimming, and diving. There were no official interscholastic sports

competitions for women in those days, but Myrtis Lee competed in intramural

sports and some unofficial interscholastic meets. She received her master’s degree at LSU, and

went on to teach, and take additional graduate courses there. For at least one year, she was director women's intramural sports (there were no Intramural women's sports in those days).

Vera was the first of the sisters

to fall in love. She met Pete Ballis,

who played end for the Tigers, and the two began a life-long romance. They were secretly married for two years (I

believe) because the terms of his football scholarship forbade marriage. My mother never told me about their “secret marriage” (apparently afraid it

might set a bad example). Therefore, I

never heard stories about a how the sister-roommates managed to hide a secret

marriage, but I can imagine.

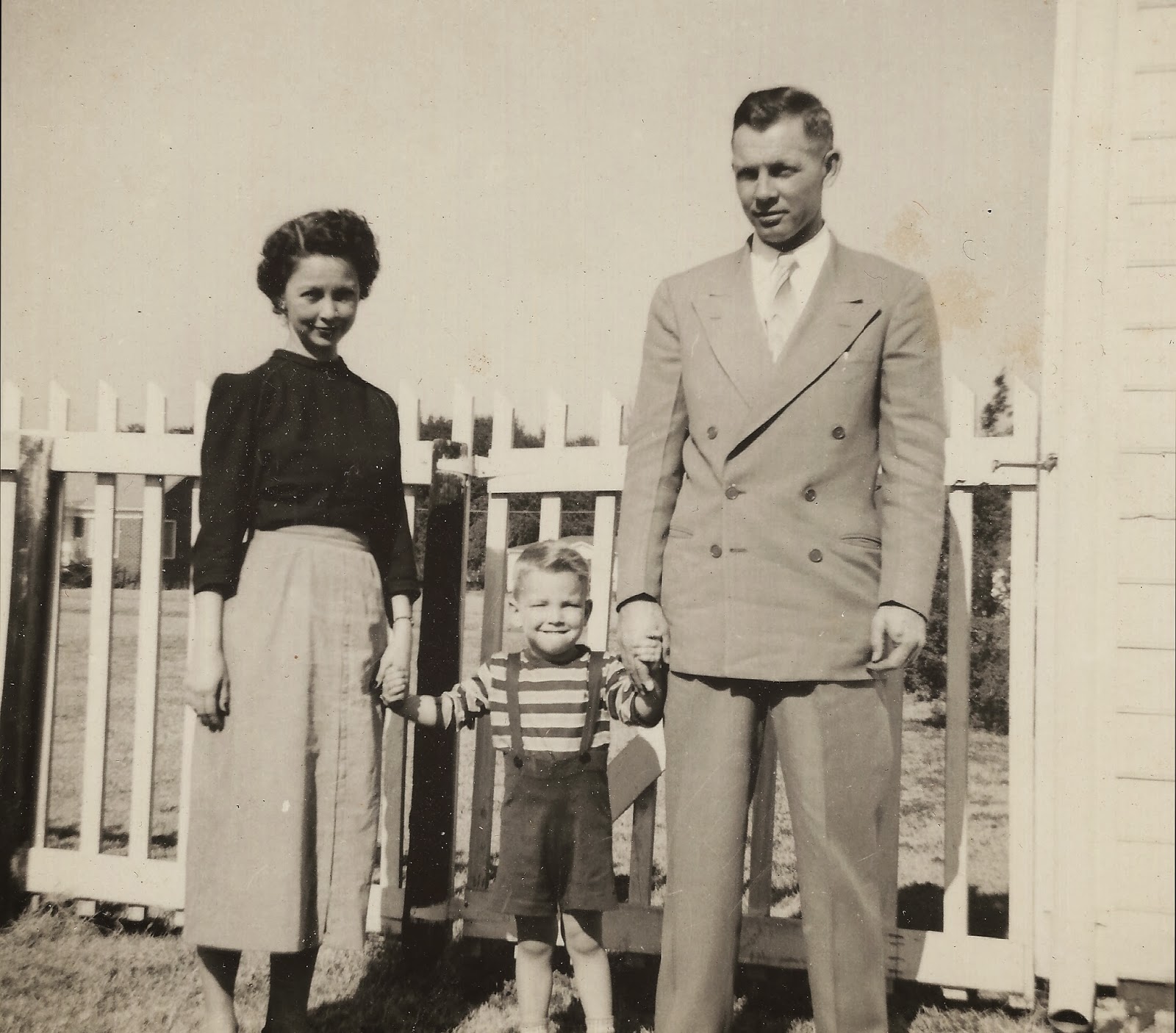

My Father, Wilmer H. “Jack” Jackson was in his late 20’s when

he met Myrtis Lee. He had completed

business school, and then four years of college at Northwestern State Normal,

and taught for several years before entering graduate school at LSU. He majored in chemistry, and was teaching, coaching

basketball, and acting as Principal at Fairview Alpha High School when he met

the little red-head he was to marry.

Jack (as she called him) attended

graduate school at LSU during the summers, and worked during the school

year. He was an athlete, having played

basketball (point guard), football (end), and baseball, and run track at

Northwestern. I always believed that their mutual love of

sports initially drew them together.

Jack spent as much time as he could (when not in classes) around the

coaches and basketball players at LSU.

Myrtis Lee spent time with the same crowd, so their meeting was not

unexpected.

The distance between Coushatta and

Baton Rouge was an impediment to their courtship. However, there was another courting couple,

Anna Mae Posey (a teacher in Coushatta) and Lester Vetter (a student at LSU,

later state representative and mayor of Coushatta) with a similar problem, and

the two couples made many trips together. The long distance courtship ended in Nov.

1938, when Jack and Myrtis Lee were married in Pitkin, LA. Their lives always operated on the School

Calendar, and they married over the Thanksgiving Holiday. Each completed their teaching contracts for

that fall semester, but that did not prevent them from conceiving their first

child – me.

Myrtis Lee abandoned her career at

LSU, and moved to Coushatta, where the couple lived in a boarding house while

their new home was built. They moved

into the frame home not long before my birth, on Oct. 29, 1939, just a few

weeks short of their first anniversary.

In the fall of 1940, Mother began teaching at Fairview Alpha School, where

her husband was Principal and basketball coach.

She taught English, and encouraged girls to participate in sports.

Jack and Myrtis Lee were teaching

at Fairview the following fall (1941) when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

drew the United States into the 2nd World War. Wilmer was 32 at the time, and was teaching

agriculture as well as science. He was

given a deferment in the draft because he provided essential veterinarian

services for farmers in the area – vaccinating animals, inspecting sick

animals, and checking for potential disease outbreaks in animals and

crops. The fact that two of his Uncles

were serving on draft boards in Red River and Natchitoches Parishes probably

helped him, but he worked long, hard hours for the duration of the War. Some of my earliest memories are of going

with him to farms where he would vaccinate cattle, horses, sheep, and

occasionally hogs. On one of these

visits, I remember seeing a cow with rabies.

It was the only time I saw my Daddy put an animal down. He did it immediately without making sure

someone took me away. I also saw a cow

with lockjaw (Tetanus). His experience

with this infectious disease frightened my Daddy so badly that he had me

vaccinated every time I got a scratch. I

must have taken 50 tetanus shots before I was ten.

In November of 1942, just as US War

involvement was ramping up, my brother Wilmer H. “Jacky” Jackson, Jr. was born.

Daddy was hunting when Mother went into labor, and she had to wait for

him to get home. The doctor was in Natchitoches. Jacky weighed over 8 pounds, and it was a

hard delivery for Myrtis Lee. Years

later when she had a hysterectomy, the surgeon discovered internal tears that

had not been repaired, and told her she would not have been able to have more

children. However, the birth frightened

Jack so much that he decided that two children were enough.

While her husband did not serve

overseas, Myrtis Lee had four brothers (Glenn, Meredith, Alton, and Lindsey)

and three brothers-in-law (Clint Jackson, Johnny Jackson, and Pete Ballis) in

the military. They served in the Army,

Navy, and the Air Force (after it was created).

As a child, I remember watching the long lines of military trucks in “convoys” driving along the highway in

front of our home. There were huge

trucks filled with materials and men.

There were even trucks carrying tanks and aircraft.

During this time, Myrtis Lee became

close friends with Isabelle Lorain Page, who would become her sister-in-law in

1945, when she married Clint Jackson.

Their friendship is documented in the many letters they exchanged over

the years. In the weeks before Myrtis

Lee and Jack were married, Page wrote Myrtis a letter each day. Theirs was a beautiful friendship that lasted

until Page’s untimely death in 1963.

Myrtis Lee’s other dear friend

during this period was her next-door neighbor and Aunt by marriage, Lizzie

Adams, wife of Andrew Adams (brother of her mother-in-law, Ida Belle Adams

Jackson). Aunt Lizzie, Uncle “Ander,” Doris, and Sarah Glen lived

across the highway from us. Daddy bought

the land on which our house was built from his Uncle Andrew Adams.

On the corner, catty-corner across

the road from our house were one of our two other neighbors. The father in this family had a drinking

problem, and on more than one occasion beat his wife. Once, when Daddy was away, she sought refuge

from her husband at our house. When

Daddy returned and learned that Mother let her inside, he was angry. I witnessed the only real fight I ever saw

between my parents. (Not that they never

fought, they just made sure we children didn’t see or hear.)

Daddy was afraid that the husband

would break in and harm Mother or me in a drunken rage. He told Mother to tell the wife to go

away. Mother put her hands on her hips

and said she would not send any woman away from her door into the hands of a

drunken beast. The two of them glared at

each other. Neither gave in; and Daddy

realized that Mother would not be dictated to against her conscious. He never admitted defeat, but he knew better

than to push it further.

When we moved in, the new house did

not have indoor plumbing or electricity, but Mother was proud of the nice

closets. Electricity, through an rural

electric coop, was installed not long after we moved in. The well was located just outside the back

door, and the outhouse was a short walk away, under the big oak tree. By the time Jacky was a baby we had running

water, and an indoor bathroom, but I have great memories of the outhouse. Daddy would take me out there, and wait

outside for me. We played games. My favorite was the Three Little Pigs. He would knock on the door and say, “Little Pig, Little Pig, let me come in.” and I would reply, “Not by the hair of my chinny chin chin.” And we would proceed

through the story, with huffing and puffing, etc.

Mother and Daddy went to school

each day, and I stayed with a baby sitter.

Sometimes I stayed with my Jackson Grandparents, Mama Jack and Daddy

Jack. They spoiled me terribly. They took me almost everywhere they went to

work on the farm. I helped Mama Jack in

the garden, and went to the cotton field with Daddy Jack. However, when Daddy Jack went into the “pen” to milk or tend to the cows, I was

not allowed beyond the fence. One day I sneaked through the fence, and sneaked

up to watch him as he milked the little Jersey cow with the vicious kick. When he saw me, he grabbed a switch and

chased me all the way to the house. I

ran so fast, I ran out of my shoes. He

must have worked hard NOT to catch me since his legs were four times the length

of mine, but then Daddy Jack never actually gave me a single spank. Mama Jack had to do that when the occasion

warranted. The family always laughed about

the day Daddy Jack ran me out of my shoes.

When I didn’t stay with Mama Jack, a

young neighbor woman kept me. Sometimes

she would take me to visit her parents.

Her Daddy had a big garden, and he grew this plant with soft green fuzzy

leaves. It was tobacco, and he grew it

for two reasons. Tobacco was poison to

insects and they avoided it. By planting

it in his garden, he kept pests away from his vegetables. Even though it killed insects, he dried and

smoked and chewed his own tobacco. I was

fascinated.

After Jacky was born, Daddy’s Aunt

(my Mama Jack’s sister) Mary Ann Adams Jackson Nelson kept us. Aunt Mary Ann’s first husband was Daddy

Jack’s brother. The Adams sisters

married the Jackson brothers in a double ceremony. However, Aunt Mary Ann’s husband Anscar

Jackson and their son Alon both died of “swamp

fever,” probably typhoid. Alon was

just a little older than Daddy, and they were playmates growing up. They didn’t let Alon start school until

Daddy was old enough to go along with him.

Daddy told about playing in the cotton barn with Alon before the cotton

was baled. They were jumping from the

rafters into the cotton, and Alon dropped hard and disappeared beneath the

cotton. Daddy tried digging him out and

couldn’t. He ran for help, and by the

time they dug Alon out, his lips were turning blue. He survived that scrape, but succumbed to the

fever. The loss of his playmate was very

hard on Daddy. It showed whenever he

talked about his double first cousin.

Our only other neighbors were the

Lindsey family. Their son Loren was my

best friend and playmate. His mother

sometimes kept Jacky and me when Mother and Daddy were at school. Loren was a little older than me, and the

leader in all our adventures and escapades.

Mr. Lindsey was a great fisherman, and we often ate fish at their house. I felt so grown-up when he let me pick out my

own fish. Now I realize he only gave us

buffalo ribs with no small bones. One

day Loren and I found an old abandoned automobile in a field. We found the axel grease in the wheels, and

began dipping it out with our fingers, and playing with the sticky, oily, black

stuff. I think we painted one

another. Any way, when Mrs. Lindsey

found us we were covered. She filled washtubs

with cold soapy water and washed us for hours.

In spite of her best efforts, my white hair remained dark for several

weeks. Loren went to school in Coushatta

while I went to Fairview Alpha, so we weren’t schoolmates until years later at

NSU.

After Jacky was born, Mother spent

a lot of time with the baby, and I spent more time with Daddy. In the summer and after school, he often took

me with him when he went to visit farms to care for animals. He also took me with him to visit with his

Uncle Edward Adams, Aunt Myrtle and their son Lemoyne. Lemoyne was 7 years older than me, and I

adored him. I would play any game he

invented. Among other things, he taught

me to ride goats, or at least to hang on to their horns until they threw me

off. When Daddy went places with Uncle

Edward and Lemoyne, I often stayed with Mary (the housekeeper) and played with

the children of the farm workers. I

loved this. Before starting school, I

had few playmates, and at Uncle Edwards, there were lots of kids to play

with. I came to believe that June Teenth

was the biggest, the best, and my favorite holiday of the year.

Mother and Daddy had very different

racial attitudes. Mother was raised in a

part of Louisiana where there were almost no Blacks. She was grown before she encountered anyone

of another race. Daddy was raised in

cotton country where there were more Blacks than Whites. His closest neighbors were Black, and his

best friend growing up was Black. Mother

was hesitant and uncertain around Black people, while Daddy was as comfortable

with one race as the other.

Uncle Edward had a pack of dogs

that were mostly kept in pens. He had

bloodhounds and other ground hounds, as well as air hounds. He also had “catch” dogs (mostly Catahoulas) that could hold the prey at

bay. His hounds were mostly for hunting

deer or hogs in the swamps. He also had

some fine bird dogs (for quail and pheasants), and some duck dogs for

waterfowl. Occasionally one of the bird

dogs would become a pet and be kept in the yard. The same was true of his favorite squirrel

dogs, usually small mixed terriers called “Fice.” Uncle Edward had a big hunting horn made from

a bull’s horn. When he blew it, the dogs

knew they were going hunting and they would go wild, barking and howling and

jumping. Sometimes he would let me try

to blow that horn.

People were always giving Uncle

Edward small, orphaned animals. For many

years he had a little herd of pet deer in a side pasture with a high fence. I remember helping him feed a small fawn from

a big milk bottle. The fawn could pull

so hard, she would almost jerk the bottle from my hands, and every now and then

she would “hunch,” and almost knock me over. Giving a bottle to a fawn is not easy. The King of this herd was a big buck named

Bill. Uncle Edward was the only human

Bill respected. When he was a fawn,

Uncle Edward gave Bill cigarettes to eat, and that deer became fond of

tobacco. When Bill grew big, Uncle

Edward loved inviting an unsuspecting victim into the deer field. The big buck would go straight for the

package of cigarettes in the man’s shirt pocket. If the man resisted, Bill would rear up and

literally take him to the ground to get the tobacco. Uncle Edward considered this a great joke.

On another occasion, a neighbor

brought Uncle Edward a litter of orphaned baby skunks. He had their “scent” glands removed, and raised them like cats. He decided to give one of the weaned baby

skunks to me, and I was delighted. I can

still remember my Mother’s reaction to my bringing home that baby skunk. I cried and pouted for weeks because she

wouldn’t let me keep my skunk.

Uncle Edward loved teasing my

Mother. She was a favorite of his, with

just enough temper to make teasing fun.

When I was really little, he delighted in teaching me curse words. He would only teach me one at a time, and

then wait until I used it in front of Mother.

I eventually caught onto the game, and learned the new words, but didn’t

use Uncle Edward’s words in front of my Mother.

About the time my brother was big

enough to go places with our Daddy, Daddy realized I was able to understand

what the men talked about. He decided I

was too old to go with him on his rounds.

I was crushed. This was the

first, and the most awful rejection of my life.

However, I had a bit of revenge.

My brother wouldn’t go with Daddy.

Daddy tried, but Jacky was very much a Mother’s boy, and he would not go

with Daddy without Mother. Instead,

Daddy went off alone, and I had to stay home with Jacky and Mother.

I started school when I was 5, and

rode to school every day with Mother and Daddy.

We would drop Jacky off at Aunt Mary Ann’s. We had to get to school more than an hour

before classes started, because Daddy coached basketball, and the team

practiced before school most of the year.

They didn’t have a gym, but played outdoors on a clay court. They usually had only 11 or 12 players, and

whoever was left when they scrimmaged had to baby-sit me. I learned to pass and dribble when I was

still mastering the alphabet and counting.

In spite of their lack of a gym or fancy facilities, Daddy’s team won

the Class C State Championship in 1948.

Mother taught English in the High

School. The gap between our worlds was

large, and I knew little about her as a teacher, but she brought stacks of

papers home, and graded them after Jacky was put to bed. Daddy was given the task of reading me to

sleep. I especially remember a book

called “The Twin Grizzlies of Admiralty

Island. Daddy didn’t read “down” to me. He read real books with real stories. He had the beginning readers at home, and I

read those long before I started school.

No one (including me) was ever sure whether I memorized the books or was

really reading the words. At some point

there was no difference, I had learned the words and began reading to Jacky.

On Sundays, we attended church at Zion

Baptist Church near Fairview Alpha School. Mother’s family had been Methodist,

but when she was growing up, there was no Methodist Church in Pitkin, and she

attended the Baptist Church. She was a

dedicated Baptist all her life. Daddy

was raised a Baptist and became a Deacon in his later years. Sometimes I thought that Daddy married Mother

so she would keep him on the straight and narrow when he was tempted to

stray. It certainly turned out that way.

The Minister at Zion was Rev. Ben

Joiner, Sr. Bro. Ben was a powerful preacher, and could

become dramatic and intense in his sermons.

I best remember his preaching the end of the World. According to my memory, (and this was before

I was 8) Brother Ben had studied the Book of Revelation, and calculated the approach

of the End Times and the Second Coming.

He gave us the date and we began to prepare. When the day came, I was very let down, but

noticed that the adults weren’t too surprised.

I think the seeds of my skepticism were sown then.

Looking back over those years and

others that followed, I realize that my parents had an unusual

relationship. They shared almost every

thing, working together at school all day, and raising their family together. They had mutual friends, common interests,

and shared daily experiences. Very few

couples (outside of farmers) share as much of their daily lives. They especially shared a love of sports. They never missed a game played by their

school, and they attended college games whenever possible. When I was young, they listened to sporting

events on the radio, equally intense in their mutual concentration, seeing the

action in their imaginations, and sharing their reactions. Later when we had television, sports were the

most watched programs. In their later

years, when Daddy’s hearing failed, they would usually turn the sound down and

just watch. Sometimes Mother would have

the radio on, listening to one game while watching another. From time to time she would give Daddy a

score or report action from the second game.

After Daddy’s death, Mother continued to watch sports. Occasionally, she would tell me what Daddy

would have said or thought about some action in the game.

That 1948 State Championship was

the climax of Daddy’s coaching career.

That summer we moved from Red River Parish to Logansport, and began a

new chapter in our lives.

TO BE CONTINUED.